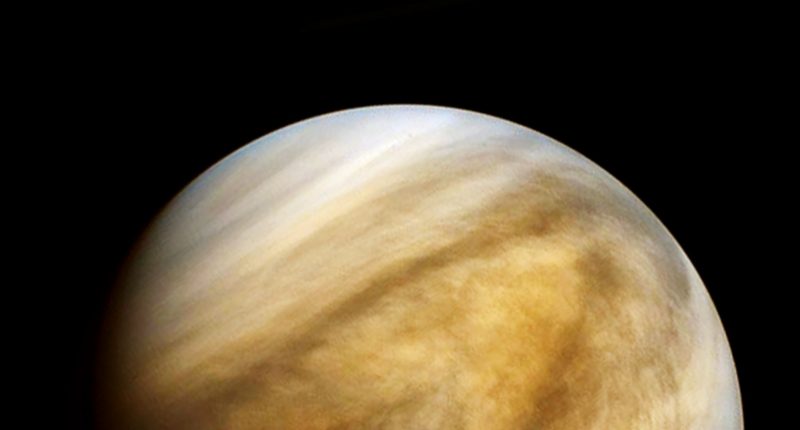

For quite some time, the space agencies of the world (namely NASA and SpaceX) have been preoccupied with Mars, and their ‘perseverance’ has yielded success. Now, it is time to turn to Venus, our closest yet perhaps the most underrated planetary neighbor. Venus is similar in structure but slightly smaller than Earth, with a diameter of about 12,000 kilometers (7,500 miles), and NASA has announced plans to return to the hottest planet in the solar system after decades.

NASA’s new space administrator Bill Nelson announced the plans of launching the missions between 2028 and 2030, to study the atmosphere and geologic features of Earth’s so-called sister planet, namely to understand how it reached its current state (“capable of melting lead at the surface,” Nelson said) when it may have been the first world in the solar system to sustain life.

The missions would be the first to reach Venus after Magellan in 1990. Both of them have been awarded $500 million in funding each. Nelson said that the missions, named DAVINCI+ (Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble gases, Chemistry, and Imaging) and VERITAS (Venus Emissivity, Radio Science, InSAR, Topography, and Spectroscopy) would offer the “chance to investigate a planet we haven’t been to in more than 30 years.”

These missions were chosen following a competitive, peer-reviewed process, based on their potential scientific value and the feasibility of their development plans. The project teams will now work to finalize their requirements, designs, and development plans.

The purpose of DAVINCI+ will be to measure the composition of the atmosphere of Venus to better understand how it formed and evolved, as well as determine whether there was ever an ocean on Venus or not. DAVINCI+ will be precisely measuring the levels of noble gases and other elements to learn how the greenhouse effect (which makes the surface of Venus at temperatures hot enough to melt lead) came into being. It will also return the first high-resolution pictures of Venus’ unique geological features known as “tesserae,” which may be comparable to Earth’s continents, suggesting that Venus has plate tectonics as well.

On the other hand, VERITAS will map the surface of the planet to determine the planet’s geologic history and understand why it developed so differently than Earth. VERITAS will orbit the planet with synthetic aperture radar, charting surface elevations over nearly the entire planet to create 3D reconstructions of topography to confirm whether volcanoes and earthquakes still occur on the planet.

VERITAS will also be tasked with mapping the emissions of infrared from the planet’s surface to map its so-far unknown rock type, as well as determining whether active volcanoes are releasing water vapor into the atmosphere.

“It is astounding how little we know about Venus, but the combined results of these missions will tell us about the planet from the clouds in the sky through the volcanoes on its surface all the way down to its very core,” said Tom Wagner from NASA’s Planetary Science Division. “It will be as if we have rediscovered the planet,” he added.

The Tech Portal is published by Blue Box Media Private Limited. Our investors have no influence over our reporting. Read our full Ownership and Funding Disclosure →